Continued from Part 1.

Episode 11 of BoJack Horseman Season 5 is the crux of the titular protagonist’s hallucinations. Every metaphor and symbol utilized thus far explodes in this dramatic, eclectic, and strangely musical season finale. Diane kicks too hard at BoJack’s soft spot. BoJack’s denial of his own trauma and consequential actions causes him to suppress even deeper before exploding like the balloon at the premiere party. Paranoia and suspicion link hands and twirl, their spiraling path decorated by music, humor, and colorful memories.

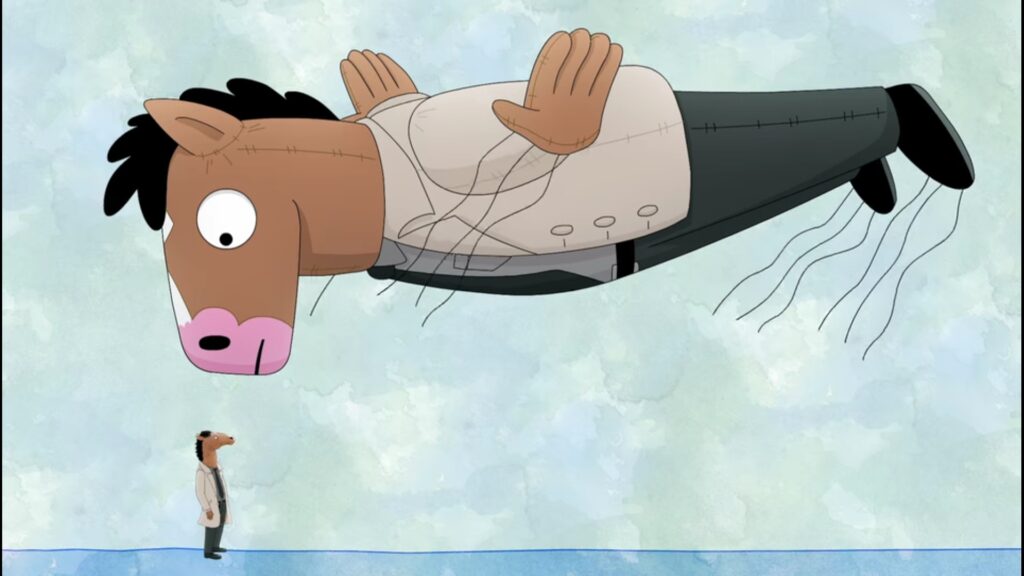

The episode begins with the opening credits, but not the usual elysian supercut of BoJack’s life. Instead, we are met with the theme song of Philbert, emphasizing the integration between both characters. This isn’t BoJack’s life anymore—it’s Philbert’s. While driving around with Gina and having paparazzi snap photos of their celebrity life, he says: “…but I still have this little rancid itch saying something isn’t right. It’s like there’s always something lurking just beyond the horizon”. The giant balloon used as Philbert promotional material, the same one Diane accidentally lets go of at the premiere party, surfaces in the sky, “just beyond the horizon”. It is this act that symbolizes the end of their friendship.

BoJack’s “lurking” feeling is Diane, who represents his confrontation of his history and hence the end of it all: his fame, sanity, and illusory good conscience. How Diane let the balloon go also hinted at their falling out. She’d intentionally kicked a cardboard figure of BoJack in frustration, accidentally knocking over the sandbag which held the balloon down. One by one, the strings were let go, and the balloon flew away.

Perhaps Diane had kicked too hard in more ways than one; probing upon things she wasn’t meant to know. Things had already slipped from her grasp before she could even realize.

This meaning, however, is different for BoJack. The balloon surfacing at the end of the scene could symbolize his regret and shame over his fight with Diane. Choosing the balloon to represent this is interesting from a writer’s perspective: playing Philbert is his only escape from reality, yet the balloon signifies the looming threat of reality itself, and the consequences of his actions if not dealt with.

The parallels between BoJack and Philbert’s life are continuous in Episode 11. BoJack voices his suspicions to Gina that the story he is acting out is taken directly from his own life. Paranoid, he begins making random assumptions and copying Philbert’s lines from the script. Scenes begin to merge, and when a scene from Philbert plays, the colors are slightly desaturated to signify the integration. This indicates that his life and the character he plays are unifying, making it harder for the audience to differentiate what is real and what is not, much like BoJack himself. The lines are blurred intentionally: the voiceover that Philbert does in the show to narrate the story is being translated in the story of BoJack.

After waking up from a cold sweat in the middle of the night, BoJack rushes to the bathroom to take more pills and begins to hallucinate again. A spotlight shines on him, perhaps to signal both his fame and his inability to escape the past. A staircase appears, connotative of a stairway to heaven as he is led up to the bright light, signifying death as well. The juxtaposition of the stereotypical portrayal of heaven as “utopian” with BoJack’s own spiraling behavior furthers these paradoxical comparisons. It is Gina who snaps him back to reality, echoing the truth that he’s bringing the character home with him.

After making breakfast the next day, BoJack spots a piece of paper slipped under his door that reads: “You did a bad thing, and I’m going to tell”, written in the classic cut-out letters of magazines. Although we later find out that it’s merely a promotion poster for Philbert, BoJack fully believes that someone is threatening him, which sends his paranoia into full momentum. The audience is made to sympathize with him here. As we were also unaware of the poster’s benign nature, we experienced the same feelings of fear and anxiety in real-time, maximizing the hallucinatory experience intended by the showrunners.

This episode is carefully structured to resemble one of Philbert, with Todd performing advertising skits and breaking the fourth wall to confuse the audience. And with BoJack in costume throughout, the clever use of both his and Philbert’s lines as transitions further serves to blur the lines of reality, with the balloon returning sporadically as an omen of what is yet to come.

BoJack’s hallucinations represent his past guilt, and this is best portrayed in the peculiar musical scene co-starring Gina. It begins with BoJack confronting Todd about the lack of ad sales before a cardboard cutout of Fritz (Mr. Peanutbutter’s character) starts ominously approaching him. In a panic, he hides. Todd tries to calm him down, but the delusion has already taken hold. He touches Todd, who instantly morphs into a cardboard cutout. Everything goes dark as Gina appears, dressed in an old-fashioned detective outfit. She sings, accompanying BoJack’s hallucinations in number. This possibly signifies the dream she once had of starring in musicals—dreams that were run to the ground by BoJack himself, yet another indicator of his guilt. It is worth noting that the song she sings was previously sung by Sarah Lynn during BoJack’s suicide attempt in Season 6, Episode 5 (“The View From Halfway Down”), this time with altered lyrics.

Gina’s abrupt appearance is a manifestation of BoJack’s guilt and inner turmoil, and when she sings “The audience is everyone you know, my friend”, people casted to play BoJack’s friends (rather than the friends themselves) appear, again emphasizing his weakening grip on reality. Everything is a movie, and he is simply saying the lines and acting out the movements of his character. His life is spiraling, and he is holding on to the slipping facade of Philbert to keep him sane. Gina continues, singing “leave them with a smile while you go” as she holds fake-Sarah Lynn’s hand and dances with her. The scene changes to the exact moment she died: in the planetarium in Season 3, Episode 11 (“That’s Too Much, Man!”). These lines and scene changes are not coincidental—they are a direct representation of the guilt BoJack feels as he, in a sense, killed Sarah Lynn. The next scene morphs into cardboard movie sets of his life: his house, Herb’s house, the boat from Charlotte’s hometown, and his mother’s summer house, all indicative of BoJack’s dissociation from reality and embracing of a sensational, fictional stage act.

Gina sings “Why not sell your sadness as a brand?”, which is what he’s been doing since the start of Season 1: turning his sappy, tragic yet controversial life story into a memoir for profit. Acting is all he’s known, whether it be for a movie or his real life. The lyric “No, you can’t stop dancing till the curtains fall” is reminiscent of the message pressured onto him by his mother, contributing to his need to perform. He can’t let anyone in until the curtains fall; he can’t stop performing until no one is watching. In the next sequence, an actress playing his mother dances into a coffin, signifying his mother’s death and her final performance in Season 6. The balloon from the Philbert premiere appears, going haywire and crashing into BoJack, yet another metaphor for the show collapsing in on his life. What’s interesting about this scene is that when the balloon collides with him, he is pushed onto a glass screen that breaks. This signifies the artificialness of his life: always acting, always behind the TV screen, forever unable to break the fourth wall of his own life to register reality.

Waking up from the hallucination, BoJack pulls out the “blackmail” note, which Gina reveals is the marketing flier for Philbert. In the show itself, Philbert actually sends himself the note out of guilt. This parallel is important as it unveils BoJack’s own feelings: he is projecting his self-accusations onto the note, attempting to frame it as though someone is trying to blackmail him when in reality, he’s blackmailing himself.

During a filming session for the show, BoJack loses control, strangling Gina before being overtaken by his delusions. As before, he goes up the staircase, this time walking into the light. An eerie echo of the blue stairs from The Truman Show appears, referencing the scene where Truman, the protagonist, found out his entire life was orchestrated for the entertainment of others. The balloon reappears, making its last symbolic entrance as a representation of BoJack’s immense, blown-up guilt as it floats above him menacingly. The parallel here—of BoJack’s ascension in the steps of Truman, both characters living in a scripted un-reality—tells the audience that the balloon, BoJack’s guilt, is his own Truman door, leading us to realize he is too far gone to distinguish freedom from reprieve.

Episode 12 is more conclusive than chaotic. With the help of Diane, BoJack checks into rehab. He says, “What if I get sober, and I’m still the same awful person I’ve always been, only more sober?”, indicating his assumption of substance abuse being the root of his problems as opposed to a symptom of it. The episode ends with BoJack finally admitting that he needs help, bringing the season to a satisfying finish.

Season 5 of BoJack Horseman was incredibly well written, with an overflow of metaphors and symbolism from previous seasons packaged into the hallucinations of playing Philbert. It is the epitome of BoJack’s guilt meshed seamlessly with his struggles of substance abuse. Every line, every action, and every odd figure seen in his delusions are cleverly crafted to create this extended metaphor and depth to BoJack’s character. The wacky, off-beat tone of this show continues to conceal profound life lessons, and its characters are far more than two-dimensional, talking animal heads. BoJack Horseman is so much more than it seems, and it is undeniably a masterpiece: a dark comedy perfect for this generation.