Airing in 2014 for a total of six seasons, BoJack Horseman is a wacky animation filled with everything from crude humor, substance abuse issues, political matters and even mental health awareness. With its serious undertones juxtaposed by quirky humour, BoJack is captivating to watch and has been one of my favourite shows to analyse as it parallels reality incredibly well, especially with the Sarah Lynn arc. BoJack is the character that you root for yet hate; this is cleverly highlighted in season five, where his reality begins to fall apart after getting casted in a TV show called Philbert.

For those who haven’t seen the show, here’s a little synopsis. Season five dives straight into filming for Philbert, a show starring BoJack Horseman, Gina Cazador (his coworker), Mr. Peanutbutter, and Princess Carolyn as the producer, among others. The show follows two detectives and their complicated, intertwined lives filled with secrets; although it’s unclear what exactly Philbert is about, it goes on to become a great hit. Meanwhile, BoJack spirals into an uncontrollable addiction to pills throughout filming. While falling deeper and deeper into addiction, he becomes paranoid, confusing his real life with Philbert’s (his character’s) life. They soon become entwined, revealing BoJack’s deepest fears. What really drew me to analyse this season is how well the writers of BoJack Horseman managed to depict his struggle with himself through playing Philbert as a character. Every little detail, every single line is so well thought out to truly portray BoJack’s internal struggle and deep hatred for himself.

The first episode opens on the set of Philbert, which looks exactly like BoJack’s own house. We’re immediately already seeing the significance and similarities of the two characters. When BoJack questions this creative decision, the director, Flip McVicker, says that “the set was designed to reflect Detective Philbert. Spare, lonely, precariously balanced on a hill of his own isolation”. This is the first parallel between them, as it also perfectly describes BoJack himself, and it clearly bothers him too. BoJack asks his coworker Gina, “Do you think I’m right, and the Philbert character is poorly written, and Flip needs to write him better so I don’t look so bad?”.

The parallels are emerging, but not quite fully realised yet. He fears that he is Philbert, hence his resistance to playing the character as to not add fuel to his self-doubts. BoJack says that “I don’t like [Philbert]… he’s a drunk, he’s an asshole, I don’t want to be him”, to which Princess Carolyn replies with “Maybe don’t be the drunk asshole… and then you put on the Philbert costume and you pretend to be this other guy. And then when you’re done shooting, you take off the costume, and you’re BoJack.” The irony in this sentence is that everything that she says is what BoJack fears, which eventually comes true. He never takes off the costume. He’s not pretending anymore. He is, or more accurately, becomes the drunk asshole.

Episode seven is where BoJack’s guilt and mistakes start creeping in following his interactions with Diane, his long-term friend who’s seen him in all his glory and defeat. The two of them quarrel over his encounter with Penny back in season two. Penny is the teenage daughter of BoJack’s friend, Charlotte, whom BoJack had near-sexual encounters with and deeply regrets it. After the fight, she holds it over his head and deviously intertwines the event into the show’s script, watching as BoJack slowly realises his life is being played out. This is the beginning of the most obvious intersection between the characters: Philbert becomes BoJack, and BoJack becomes Philbert; they are one. The words they’re both saying, scripted or not, are simultaneous.

Perhaps the greatest heartbreak of the season is when Hollyhock, BoJack’s younger half-sister, is burdened with the responsibility of taking care of him. When BoJack picks her up from the airport, he’s already in costume; when they get home, Hollyhock accidentally throws away his pills, sending him into a rabbit hole of desperation. He strings her along to get more pills, even going to the extent of breaking into Gina’s house. He throws away his time with Hollyhock, whom, in previous episodes, seemed to mean a lot to him—addiction acts as the double mirror that he can’t see through while Hollyhock can.

Despite putting Hollyhock in danger, BoJack is desperate enough to contact a drug dealer. Startled by his costume, the drug dealer asks if he’s a cop. BoJack explains himself, saying it’s just a costume from a show he’s starring in. The drug dealer responds with “Normally, people return the costume”. This is such a trivial detail, but so important to the plot. The drug dealer is right: one would normally return a costume from the set. But BoJack relates so closely to Philbert, even though he doesn’t want to be him, because he’s too afraid to make serious changes. To him, Philbert is comfortable. He’s home. And why would you leave home when you’ve never known anything else?

With everything happening at once, BoJack is bound to crack under the pressure, and he does. At the end of the episode, he never gets his pills. Going through withdrawal, he becomes jittery and incredibly desperate. So, he drives into oncoming traffic. This acts as the ultimate last resort: he knew he would get those pills if he was seriously hurt, which also explains why he was so insistent on doing his own stunts on the show even though he was told multiple times not to.

Episode 10 is where everything really unravels. The tension and avoidance has built up just for it to explode at the perfect place: Philbert’s premiere party. The episode starts off with a critic’s review: “What separates Philbert is the character’s vulnerability. This is not the sad man as suave and cynical anti-hero, but a barely scabbed-over wound of a person.” Perhaps the critic is describing BoJack. He is vulnerable—he has just healed, both mentally and physically. From his car crash injuries, from Sarah Lynn, from Penny, from everything, but just barely. The pus fills at the edge of the wound, almost ready to pop out at any second. The slightest cut from a blunt knife would rupture him—and that knife is Diane.

At the premiere, BoJack says “The most amazing thing about this show is that I’m sure we all have Philberts in our lives, or we are Philberts. You know, we’ve all done terrible things that we deeply regret. I’ve done so many unforgivable things. And I think that’s what this show says.. is that… we’re all terrible, therefore, we’re all okay.” It seems as though the reason he finds solace in Philbert is because he finds forgiveness. Through playing the character, he found an unlawful, convoluted way to forgive himself because that’s what Philbert did, and that’s exactly the opposite of what Diane wanted to achieve through ‘exposing’ him. She complains to Flip, the director, saying, “I made him more vulnerable, and that made him more likeable, which makes for a better TV show. But if Philbert is just a way to help dumb assholes rationalize their awful behaviour, then we can’t put this out there.”

And she’s right. Making someone vulnerable allows sympathy to seep in, and eventually forgiveness. But showing someone your wounds does not mean they have been healed. As the critic indirectly states, BoJack is still a ‘barely-scabbed over’ person—he has a long way to go, and Diane has ironically justified his behaviour.

The argument heats up and Diane pressures him to talk about New Mexico (Penny’s incident), which he has never directly spoken about to anyone before. This leads to everything unravelling: every incident that has happened slipping out of his mouth. He recalls the shady things he’s done, saying “Most of these women don’t even remember, I bet”, as if that makes it any better. It’s not whether they remember or not that matters; it’s the fact that he did it in the first place. He rationalises this by saying “I’m the one who has to feel the guilt all day, every day.”

There’s no doubt in this statement: he is the one who aches from the guilt, but what counts in this situation is who caused it. He goes on to say, “I’m the one who has suffered the most because of the actions of BoJack Horseman,” and again, in such a labyrinthine way, he’s right. To be hurt by somebody else is, in a sense, ‘easier,’ because it’s justified. One can find comfort in the fact that their feelings are completely warranted. But when you hurt someone else, you end up hating yourself, and perhaps there is no worse feeling than this. This is why he finds consolation in playing Philbert: he suffers from the actions of BoJack, but Philbert tells him that it’s okay.

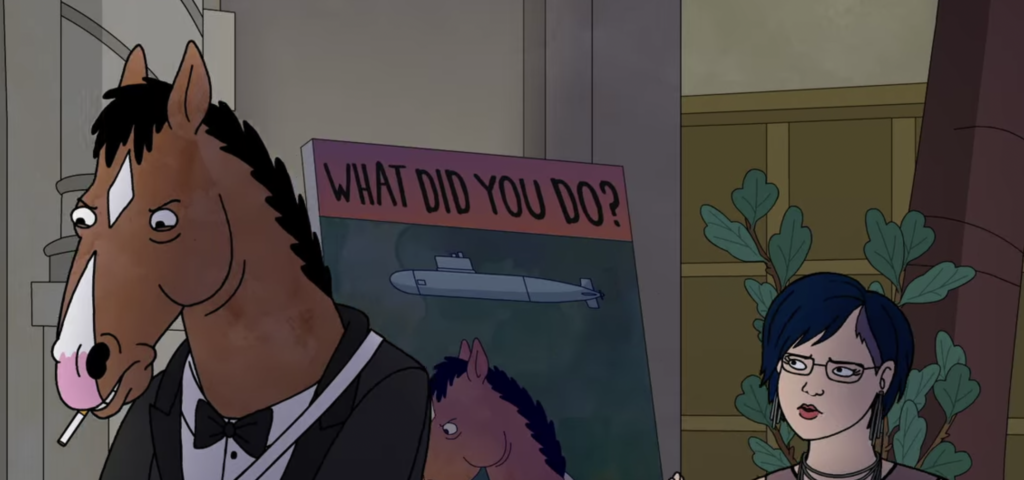

Despite being a small detail, it’s worthwhile to note that while Diane confronts him, he stands in front of a Philbert poster with the tagline “What did you do?”. This placement, especially the words and the fact that it’s Philbert himself in the poster, highlights the gravity of the situation. Furthermore, the irony is perfect: Philbert asking a confronting question despite it being the last thing BoJack wants to do. He refuses to change, emphasising this by justifying his answer and saying that when Diane wrote his book (in season one), she was the first one to tell him that as “screwed up” as he is, that’s okay.

Part two coming soon.