by Elisa Redza

Note: This article contains descriptions of unhealthy thoughts and behaviors in relation to body image.

When I was a child I liked to make a wish before I fell asleep. Most nights I wished for the same thing.

I wished that I was prettier.

I find myself at odds with beauty. Beauty is supposed to invigorate and inspire. It’s supposed to make you feel alive and in awe of life. So, I never questioned the idea that people should strive to be pretty. I thought it was part of the natural progression of life; cute child, awkward teen, maturing young adult, pretty adult and then, graying elder. I kept waiting for the magical day when I lost the ‘baby fat’ and got through my teenage acne stage. It felt weird to wish that I looked different, since I didn’t see any problem with anyone else having the same concerns. It was morally conflicting to strive, even partially, towards a beauty ideal deeply rooted in decades of inequality.

I didn’t want to lose weight just because I wanted to be pretty. I wanted to go shopping and not dread trying clothes on, already knowing more than half of them wouldn’t fit. I wanted to hang out with my friends and not think about how I might be the odd one out. I wanted to not worry about whether I could squeeze between rows of chairs when I would need to use the bathroom at school. I wanted to sit on plastic chairs without thinking they would break. I wanted to relax when people looked at my legs. I wanted to have a conversation without someone telling me how to lose weight when I didn’t even ask them to do so. I wanted to lose weight so I could live without the perpetual stress of being big.

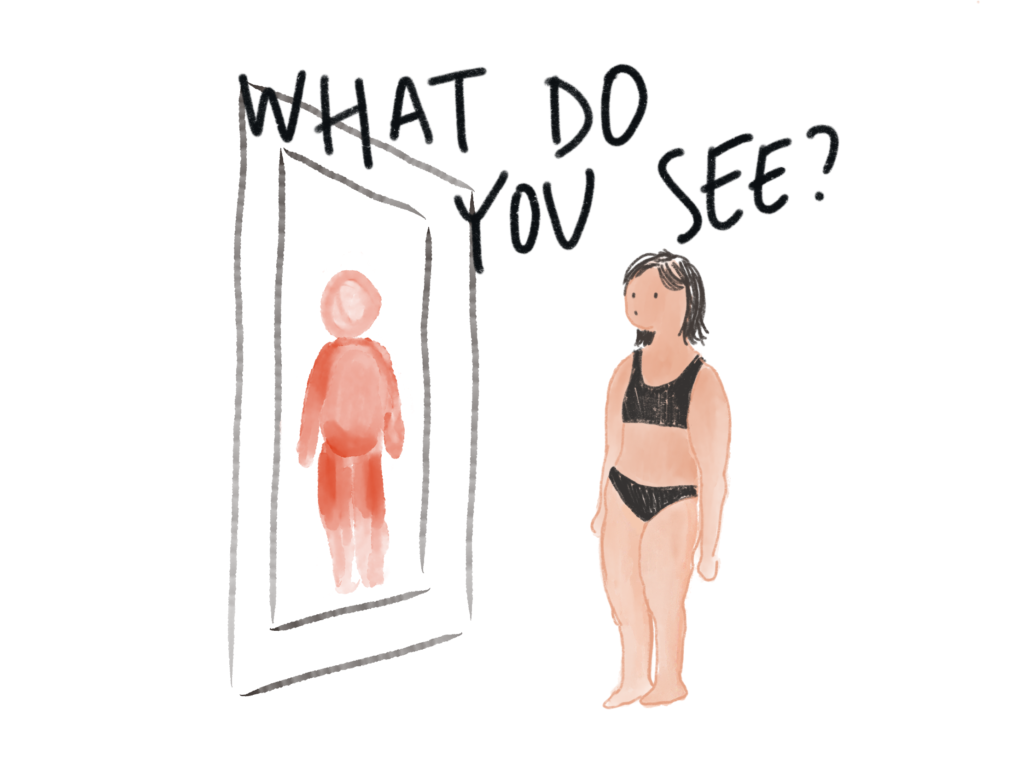

Right outside my bedroom is a full-length mirror. When I was losing weight, I looked at my body as parts that got smaller or parts that needed to be smaller. From time to time, I’d randomly measure my waist with measuring tape. If I wore pants with an elastic band, I’d stretch the waistband and see if the gap between it and my waist got bigger. Sometimes in the middle of the night, I’d just stare. I’d lift up my t-shirt and suck in my stomach. I’d lean to the side and see how many rolls formed. I’d walk until my nose almost touched the glass and study my face. By the time I saw ‘progress’ in the size of my body, I found another part of me to monitor. I’d fix my eyes on the pimples that covered my cheeks. I’d turn my face until the light hit so that you could barely see the scars. I’d run the tips of my fingers over the bumps and traced back the path when I stumbled upon a new one.

According to Leboeuf, the body positivity movement encourages people “to accept our bodies, regardless of size, shape, skin tone, gender, and physical abilities”. There has been progress in social media with people denouncing the idea of a ‘summer body’, for one. The message commonly shared today is: ‘If you have a body and it’s summer, you have a summer body.’ However, there are still a ways to go. ‘Are they fashionable or just skinny?’ came about as a reaction to the double standard put on fat people in fashion. It’s hard to believe that ‘all bodies are beautiful’ when people are still told there is a ‘right’ body for specific clothes. It also brings to light the way recent fashion trends, like crop tops and low-rise jeans, use the body as a focal point instead of the garment. People are more concerned with the body wearing the outfit than the clothes themselves. This is just one of the ways fat people are denied space. It is more preferable to hide stomach rolls or the curve of your thighs. It is considered inappropriate for fat people to wear a cropped tank but trendy for those with the ‘ideal body.’

As long as the message on body image is centered around beauty and attractiveness, I don’t see how we’ll make progress. Beauty is unattainable because of how body shapes come in and out of trend; two recent ones being ‘skinny Tumblr girl’ and ‘slim thick’. It is also out of reach for those who can’t afford to buy new clothes or get their hair done solely to fit these conceptions. People are beginning to discuss the intersections between style and class through an analysis of the ‘looking expensive’ trend. Instead of heavily focusing on beauty, we should redirect the conversation to treating all bodies with respect. Beauty is not going to solve the matter of how people feel reluctant to reach out for help because of preconceived notions of their body, thin or fat. Beauty is subjective while respect is objective; not something to opinionate on, no matter how well-intentioned. Beauty is personal, but it also has societal implications, which is why we can’t help but find confirmation in external judgments. A person’s value shouldn’t be based on something that is beyond their control.

Looking back, I didn’t “let go of myself” when I gained weight, and there isn’t a skinny version trapped inside me waiting to be set free. I didn’t do a disservice to myself when I chose not to go on a diet. Despite the wholesome aim surrounding body positivity, the movement caused me more harm than good when it came to dealing with weight gain. I looked to my friends for confirmation that it wasn’t the end of the world—it would have been, to 15-year-old me. Telling myself it was okay only reminded me of how much I disliked the fact in the first place. Body positivity still gave me a reason to stare at myself in the mirror; the only difference was that I was trying to convince myself that I was still pretty.

Body neutrality has helped me cultivate a better relationship with my body. Sai Siddhaye, who writes for The Revival Zine, defines it as “taking the important stance that inclusivity is about giving everybody the same value, care, and visibility, regardless of whether or not it is beautiful or attractive.” This mindset helped me to partake in exercise again because it was previously hard to detach it from weight loss. Body neutrality is useful for the days when you don’t feel beautiful to remind you that you still have as much value either way.

Body neutrality is both liberating and terrifying in a world that emphasizes looks. It made me come to terms with my internalized fatphobia, and the fact that I may never be ‘truly’ pretty based on external standards. Yet, it has also given me freedom. I’ve let go of a past that others seem to cling onto—I’ve given away clothes that don’t fit me; I’ve deleted ‘progress’ pictures of my acne. Personally, body neutrality seemed more realistic. It gave me the space to have different feelings about my body on any given day; it allowed me to take as much time as I needed to heal. Now, I look at myself and see my body for all that it allows me to do. The main difference with body neutrality, which people tend to point out, is that it acknowledges the privileges some bodies have over others. It recognizes that not everyone has the capacity to feel pretty. By detaching self-worth from appearance, body neutrality reminds people that it’s enough to just live.