by Allison Lee

When you’re born and raised in Penang, Malaysia, food ceases to be merely sustenance; it is a luxury, an experience, a delicate offering to the temple that is your body. Ask just about any Penangite what they are proudest of and chances are, ‘street food’ will be the answer that rolls off their tongues.

When merchants of tea, spices, and cloth set foot in Penang as a trading port in the 1800s, they hadn’t a clue that they would soon create dishes upon dishes of cuisines that would be able to warm and unite the hearts of one state. Traders and settlers originated from all over the globe, encompassing those from Europe, the Malay Archipelago, India, China, and many more; this ultimately fostered an environment akin to a melting pot.

Penang began housing people from all walks of life, speaking different tongues and craving different tastes. As one culture bled into another, a diverse heritage was born, and so were hybrid dishes. However, that doesn’t quite explain the rise of hawkers that we now see with the turn of every corner.

As it turns out, street food peddling was one of the easier forms of self-employment that didn’t require much capital to kickstart. In an effort to make ends meet back when times were less fortunate than today, many fled to the streets and whipped out their pots and pans, filling every alleyway and open road with aromatic scents designed to lure you into a trap of hunger.

Today, unfortunately, we have to ask the dreaded question: After decades of building up a culture that has such a stronghold in Penang, is that culture at the risk of disappearing in the face of the digital era, not to mention the pandemic? If so, is there anything we can do in our power as residents of the Pearl of the Orient to save our beloved hawkers?

Several years ago, when the dismissal bell would reverberate down the hallways of Chung Ling High School, Yew Yik Khai’s mother would pick him and his sister up and the trio would make for Tommy’s Nasi Padang.

YK: It is just phenomenal. Even the thought of his Nasi Padang is enough to get me craving again! Plus, he gives such generous portions and, oh god, not to mention the curries.

When asked about his other favorite hawkers around Penang, Yik Khai reminisced about Sin Hup Aun Cafe’s Hokkien mee, yet another stall he frequented to dabao (take away) lunch after school.

This feverish passion for Penang’s street food did not manifest out of thin air; rather, it was a long-brewed taste cultivated since his youth. While it’s difficult for Yik Khai to pinpoint his earliest memory of Penang food since it’s something he grew up with, he did share his favorite dish, one that many Penangites will relate to in the snap of a finger—cendol.

YK: It’s not only the dish itself but the experience of standing by the road under the hot sun with sweat droplets flowing down the side of your face. The crowd, the atmosphere… and you’re just slurping a bowl of refreshing, not-too-sweet cendol. That feeling… best la!

As we know all too well, cendol is a widely championed dessert in Southeast Asia, assembled by a tired but smiling uncle or auntie with coconut milk, palm sugar syrup, green rice flour jelly, all piled into a bowl of shaved ice. For us Penangites, however, it’s so much more than a dessert simply hitting our taste buds; just like Yik Khai said, food is an experience made that much more savory by the love that goes into creating it and the environment in which it is consumed.

AL: Totally! I think Penangites take food a lot more seriously than the average person. We are obviously very proud of our hawker and street food culture; what do you think sets our food apart from the rest of the world?

YK: I think it’s the passion our hawkers have when making their dishes. To them, it’s more than just making food; they carry our identity as Penangites. Ask any Malaysian what Penang is known for and chances are, they’ll mention [the] food. Apart from the godly flavors, the mixture of cultures, and unique combinations, you can taste pride, heritage, and passion in our food. That’s why Penang food is the best.

Of course, even though it is an element many of the state’s citizens are collectively proud of, Penang food still holds different meanings for each of us. For some, it is an escape; others, a luxurious indulgence. For Yik Khai, however, Penang food means home. According to him, whenever Penangites travel, work, or study abroad, we all make a beeline for hawker stalls once our feet land back on Penang soil.

YK: For some reason, food from home is so distinct and irreplaceable. I know for a fact that every time I eat Penang food after returning from my travels, I can feel the warmth of home.

—a sentiment that I’m sure many of us can relate to.

Speaking of being away from home, Yik Khai had studied in KL momentarily for college. When asked about the major differences between the food scene in KL and Penang, he mentioned how KL is a larger city and things tend to be more organized and structured; hence, there are fewer roadside hawkers or mobile stalls being pushed around by their owners. He talked about how it’s easier to regulate the KL hawkers that are often only found in coffee shops and food courts but ultimately rounded back to the one-of-a-kind feature of Penang’s roadside stalls.

Ever since the pandemic loomed over Malaysian skies in early 2020, a substantial portion of the population has been thwarted into financial quagmires, our hawkers included. Due to the implemented SOPs that dictated no dine-ins, people have been less keen to go out to take away their food and have slowly turned to either home-cooked dishes or takeaways via third-party delivery apps.

AL: Undoubtedly, the pandemic has worsened businesses for our hawkers; in your opinion, do you think that the pandemic is the main cause for declining hawker sales, or did it simply magnify an existing problem? Because given the current workaholic culture and digital age, a lot of people are keener to order in than drive out to hawker stalls to take away.

YK: I don’t think hawker food will ever ‘lose out’ to restaurants and cafes simply because the flavors, the atmosphere, [and] the experience of eating at a kopitiam is… unbeatable. I’m quite confident that no Penangite would last long without hawker food; however, I think that the pre-existing phenomenon you mentioned is an inevitable change.

Yik Khai proceeded to let me into his train of thought, namely that as consumers begin to prioritize convenience and safety concerns during the pandemic, this serves as an impediment toward hawker businesses. He explained that in the face of this problem, the short-term solution is to ceaselessly support dabao; in the long-term, however, it’s likely we’d have to move to digitalize the hawker industry sustainably and fairly to the hawkers to recapture lost market share and keep alive this tradition of ours.

When Yik Khai saw the hawkers sitting by their stalls with little to no business to keep them busy, he felt the urge to do something about it.

YK: Hawker food, to us locals, is what we know as ‘cheap but awesome’ food. And for the hawkers, it is more than a mere job—it is their life. It seems as though many have forgotten about hawker food or switched their eating habits throughout the pandemic. Even so, it would be a shame to see our long-standing hawker culture slowly die off; for me, that was an alarm I felt needed to be sounded.

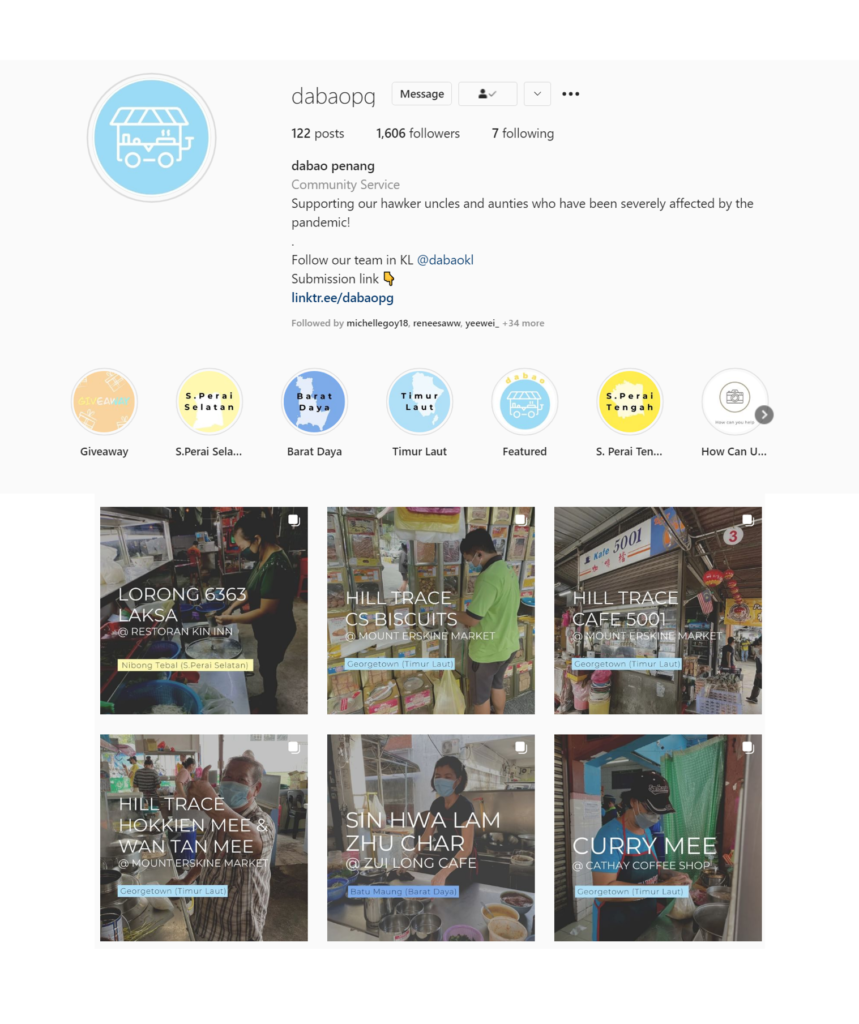

That concern and empathy for our hawkers was a seed that sprouted into a pro bono youth initiative—Dabao Penang—that acts as an advertising medium for the local hawkers through social media platforms, namely Facebook and Instagram. With a strong determination to spread the word and hopefully boost hawker sales, Yik Khai reached out to his friends and contacts and assembled a team of passionate youths who shared his vision.

YK: I guess the experience from running clubs and events and working in various organizations guided me through the set-up phase for this newfound project; you know, there is a lot you have to plan for to get a system running. As soon as we formed the team, everyone put their heads together and kept churning out ideas—it was amazing.

AL: A well-put-together team definitely gets the gear going and the train running! How about the support from your close friends and families? What do they think about this initiative that you’ve started?

Yik Khai explained that due to the uncertainty of the project’s performance, he kept the initiative to himself in the early stages. It wasn’t until Dabao Penang was more stable and established that he shared the wonderful news with those around him and received nothing but waves of support.

With his friends and family’s support and a bright, capable team, Yik Khai injected more effort into the project, determined to reach his first goal: to approach as many hawkers in Penang state as possible, with the dream of mapping out all of them on a directory map.

In the long run, Dabao Penang hopes to help hawkers of all Malaysian states, which implies expanding to other towns and cities. Just a month ago, they succeeded in launching a Klang Valley partner project, effectively spreading the hawker spirit.

AL: The inspiration behind this project is something everyone should participate in, since, as aforementioned, food is a key element in uniting Malaysians. So, how can the public contribute to the cause? How can we maintain our hawker culture apart from just buying from them?

YK: I guess the most powerful thing to do is to spread awareness, to instill [a] sense of pride and identity in our fellow Penangites. That is one very special feature we have—that Penangite pride… Once we build this sense of identity, then supporting our hawker uncles and aunties, or anyone [else] for that matter, would be helping a fellow Penangite—one of our own.

For those of you who bear a curious heart, here’s a quick rundown of how Yik Khai’s project works:

First off, the public who wants to support their project would upload photos and videos (of stall fronts, the hawkers themselves, menu and price lists, food, etc.) as well as relevant information (contact number and operating hours) to Dabao Penang’s submission form.

Then, the team extracts the information and designs visually pleasing posts to be published on their various social media accounts. To categorize the hawkers for their audience’s convenience, the team has also established color codes for Timur Laut, Barat Daya, Seberang Perai Utara, Tengah, and Selatan respectively. That way, during MCO, the public can choose to visit the hawker stalls in their vicinity to minimize travel distance.

Each submitted stall is also placed on an online directory known as their Dabao Map. This extra mile is to enable the public to search up specific dishes they are looking for and have the results narrowed down instead of having to scroll through Dabao Penang’s hundreds of posts to find what they’re looking for.

It’s heartwarming to see the youth involved in the welfare of our country, especially given the many trials and tribulations we’ve tumbled through in the past few months. Yik Khai’s project is proof that all of us can put in the effort to help our community, no matter how minuscule we might think the effect is.

What are you waiting for? Submit to them today if you’re out and about to dabao anyway. That’s all it takes to contribute toward the preservation of a Malaysian culture as old as our country itself.